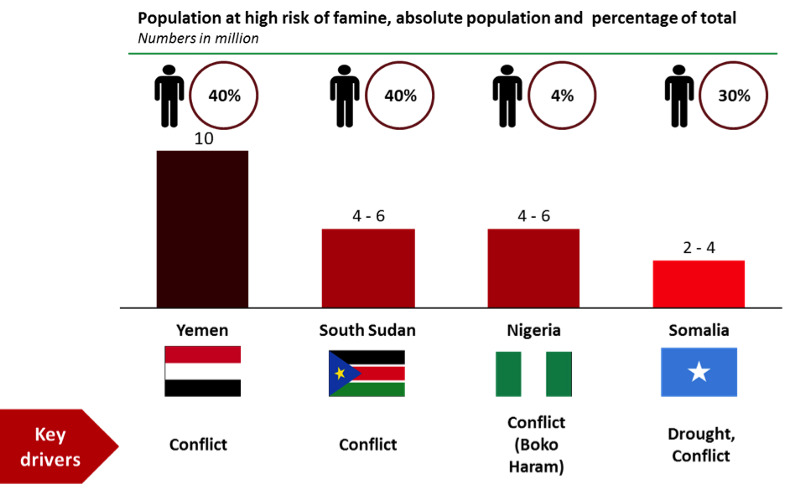

The world stands on the precipice of a humanitarian disaster. Surplus global food production notwithstanding, ~70 million people are likely to be food insecure in 2017. A whopping 20 million of these are at risk of death by starvation in 4 countries — Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia and Nigeria. The situation presents a paradox. Despite tremendous technological and social advances, why do famines persist? Turning to history gives us some answers.

Romit Mehta

Famines through history

Famines have been an intricate part of human history. In pre-colonial Tanzania for example, their frequency led to people measuring their lives out in famines. The local populace further believed that red glow at Mount Kilimanjaro’s summit presaged death by starvation, showing the intimate ways through which famines were tied to local beliefs.

Deaths from famines through centuries has been disputed due unsystematic recording of casualties and difficulties of attribution. Notwithstanding data accuracy concerns, 20th century, the time of great technological advancement, has been the deadliest in modern human history in terms of famine related mortalities which stand around 75 million. Even ignoring the deaths due to the Great Leap Forward in China (which claimed ~30 million lives) the century has claimed over 40 million lives, concentrated mainly in Europe and East Asia. South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, associated with hunger related catastrophe in public perception, have just accounted for 11% of global famine mortality in this period.

However, famines have steadily reduced over time. Europe saw its last famine in the 1940s, East Asia in 1960s, and the South East Asia in 1970s. In a cruel twist, the continent with lowest recorded famine mortalities — Africa, remains the only place where they are presently entrenched.

What causes famines?

Historically caused by a range of factors resulting in crop failures, their occurrence in modern history has taken a specific turn. Weather shocks, traditionally associated with famines, have ceased to be their primary driver. Development of modern communication and transport technologies allows rapid dissemination of stress signals and remedial actions. It would not be far-fetched to call the lorry, among the most effective anti-famine development in the recent past.

Given this, why did mortalities increase in the 20th century and why do famines still happen?

Amartya Sen’s entitlement theory is useful here. The theory, in context of famine, describes ways in which individual can procure food — growing it, working for it, buying it or being provided it. The theory shifted the narrative from a viewpoint of — too many people, limited food — to the inability of people to acquire food. This was a crucial because it demonstrated that famines could occur even in food surplus situation if individuals could not acquire food due to external shocks.

The insight from this is internalized in modern welfare states. For example, weather shocks might destroy local agriculture and create inflationary conditions which can affect people’s ability to grow, buy or work for food; food transfers can be provided by government. A standard that they are expected to meet. Which is why, Sen claimed that famines did not happen in countries with freely elected government and an adversarial press due to democratic accountability. Hence, the answer for their occurrence often lies in benign or deliberate ignorance of famine like conditions which impede food transfers.

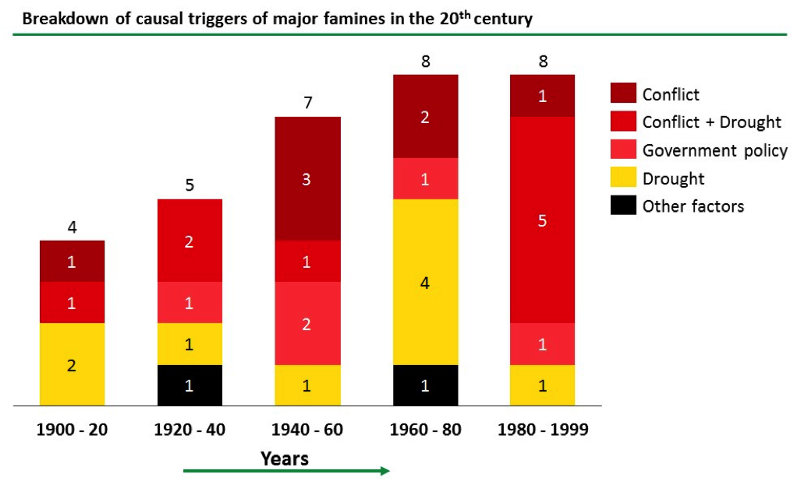

Source: Stephen Devereux, Famine in the 20th century, IDS working paper

As seen, drought by itself has not been a dominant trigger except from 1960s to 80s when Ethiopia and the Sahel region in Africa suffered adverse weather shocks. Limited state capacity or neglect (conflict, conflict + drought, government policy) has been the leading cause of famines through the 20th century.

India’s colonial history illustrates this well. Take the Bengal famine of 1943. Fearful of the advancing Japanese army from Burma, the British destroyed rice stocks and local boats. Coupled with a relatively poor rice harvest in 1942, runaway inflation followed. The initial reaction of the British was to incorrectly blame the traders for hoarding rice stockpiles and price controls and anti-hoarding drives were initiated. Once the gravity of the situation became clear, entreaties for aid were made to the War Cabinet led by Winston Churchill, to little effect. Leopold Amery, secretary of state for India best captured the spine chilling indifference as he noted, “Winston may be right in saying that the starvation of anyhow under-fed Bengalis is less serious than sturdy Greeks, but he makes no sufficient allowance for the sense of Empire responsibility in this country.” This criminal negligence resulted in a loss of 2.1 million lives. The memory of hunger through the colonial rule shaped the social contract on food security in India. As a result, the public distribution system was introduced as mechanism of food price stabilization on June 1st, 1947.

Independence of newly formed nation states in Africa, on the other hand, was associated with increased instability. Militarization, counter insurgency and civil war increased food insecurity. In the horn today, the equation; war + drought = famine, often holds true.

Food insecurity today

Conflicts, limited democratic accountability, and low administrative capacity, has fostered a situation of unprecedented food insecurity in modern history.

Over 30% of the entire population in Yemen, Somalia and South Sudan are at a high risk of famine. Unity region in South Sudan, the oil and conflict epicenter, was in fact declared hit by a famine in February which the timely intervention of aid agencies subsequently averted. Raging civil wars, conflict between international actors (Houthis and Saudi led coalition) and local actors (Boko Haram and Al-Shabab) has diminished state capacity, fostering chronic hunger for millions.

As history has shown, negligence and dereliction of basic state responsibilities can be deadly. While the aid agencies have launched missions in these countries, they only constitute a band-aid. A sustainable solution lies in democratic accountability and building capacity to deliver services. The lack of democratic accountability has led to loss of millions of lives, it is a lesson worth repeating.

Romit Mehta is an advisor to the government of Ethiopia on agriculture transformation. Views are personal