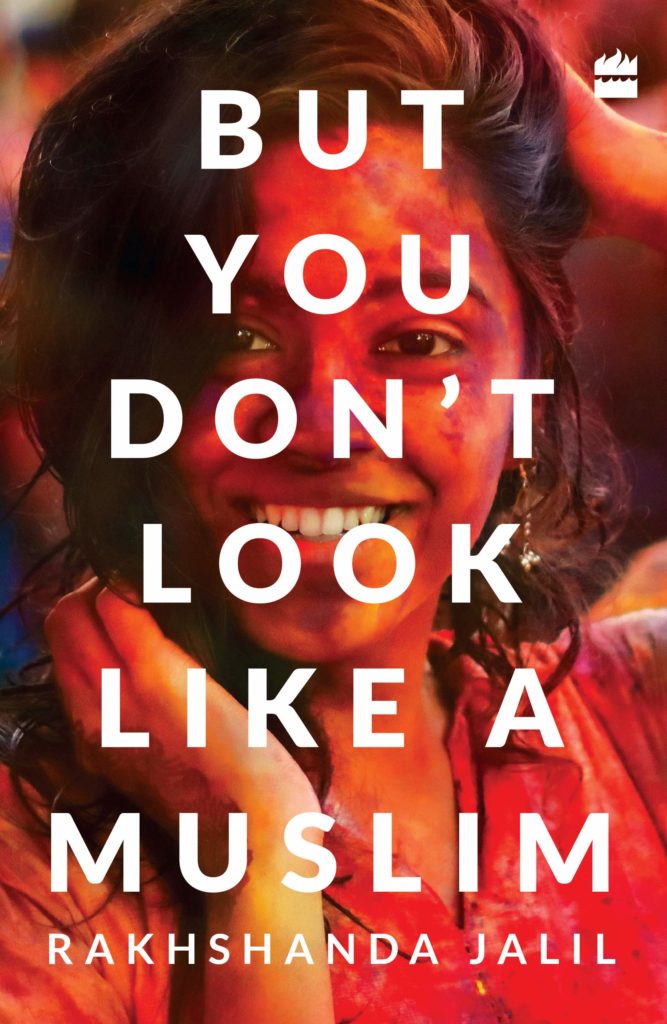

But You Don’t Look Like A Muslim

Rakhshanda Jalil

HarperCollins

Pg: 240

Price: Rs 599

This collection of 40 essays by Rakhshanda Jalil is a collection of work that has been previously published in newspapers and journals or presented at seminars. They make for absorbing reading as she explores and analyses her coming of age in contemporary India and looks at the various influences — literary, philosophical, political and personal — from an older past that have shaped and moulded her existence in a difficult, unequal, complex and pluralistic democracy.

The book is divided into four parts and the short essays are grouped as: The Politics of Identity, The Matrix of Culture, The Mosaic of Literature, and The Rubric of Religion. They make for easy, lucid reading.

This grouping is not about watertight compartments and the essays in each section interweave with those in other sections, showing how the personal is always political and cultural, and deeply influenced by the mosaic of literature and religion. All sections explore different facets of Indian life, history, literature, food, festivals and cultural practice, interspersed with poignant and memorable personal narratives and detailed research and readings on various issues.

Rakhshanda’s book celebrates both being an Indian and belonging to the Muslim middle class and tries to engage in a dialogue with India and the rest of the world through her writings as a writer, critic, translator, and literary historian.

She painstakingly examines an older heritage and history that must remain a reference point to end the deep polarisation between communities that is the reality of everyday life in India today. Her essays bring to us the world of poets, visionaries and literary figures from medieval India such as Amir Khusrau, Kabir, Akbarabadi, Abdur Rahim Khan and Ghalib, among others, who built bridges between different faiths that sustained and nourished the quotidian transactions so vital to human life.

I was unaware that the Jamia Nagar neighbourhood in Delhi had no MCD dispensary, Fair Price Shops, Safal and Mother Dairy outlets for fruits, or that delivery boys from nearby eateries, dry cleaners, chemists, grocers, and florists would not provide delivery at doorsteps.

She draws attention to how Urdu, a secular language that evolved outside of Islam, has been identified as the language of all Muslims, although the Muslims in Kerala speak in Malayalam and those from Assam speak in Assamese. She traces our inheritance of a rich oral culture in Urdu comprising dohas, sakhis, horis, jhulanas, ulatbanis, manglas and baramasahs that give evidence of pluralistic and syncretic traditions and highlights how this robust oral culture rooted in multiple contexts has been slowly replaced by a different language and a different vocabulary altogether.

Rakhshanda’s maternal and paternal families chose to stay back in India because the idea of India appealed to them far more than the idea of uprooting themselves and embracing opportunities in the ‘Land of the Pure’. Staying back was an informed choice, one in which her father “was putting down more roots, stronger and deeper into the soil that had sustained generations before him,” choosing the leadership offered by Jawaharlal Nehru over Mohammed Ali Jinnah, in the midst of mayhem and a bloody Partition.

While reading through these accounts, the thought kept running inside my head (since my life in India has run parallel to hers) that the title of this book could have easily been, ‘Aren’t you supposed to behave like a woman’?

Women in all communities lead unequal lives and seldom speak out, since no community exists in a monolithic fashion, unaltered by the markers of class and gender. It is, however, more difficult to belong to a minority community in India, and far more difficult to survive being poor with little or no access to education, opportunity, and resources.

As a young Muslim female, she walked the plank with regard to nationalism on several occasions in independent India because the religion she was born into immediately made her a suspect in the eyes of her young classmates in 1971, for instance, when she was all of eight years. To her credit, her belief in possibilities enabled her to deal with hostile surroundings in her stride. She is part of a very minuscule privileged group in India that moves beyond stereotypical Muslim, Hindu or Christian identities, carrying forward the best of their traditions to embrace the reality of being an Indian in a pluralist universe.

She provides delightful reminiscences into family events , food, festivities and records the dwindling of older extended families and community collectives into more nuclear structures. She documents the change in the patterns of living among the more privileged.

Her essays bring to us the world of poets, visionaries and literary figures from medieval India such as Amir Khusrau, Kabir, Abdur Rahim Khan and Ghalib, who built bridges between different faiths that nourished the quotidian transactions so vital to human life.

She also draws attention to the hidden and expressed communal polarisation in New Delhi, the difficulties in finding accommodation for Muslims, and the lack of access to a whole series of services that otherwise ease the stress of urban living of the majority community and is taken for granted. For instance, Pizza might not be delivered to Jamia Nagar and Muslim areas, whereas there will be no problem for the residents of New Friends Colony in the neighbourhood to get the delivery; same, perhaps, is the routine with a taxi service, among daily acts of entrenched discrimination.

Pushing oneself to wear “identity as a badge of courage instead of shame,” I always believed was not a life choice that constrained followers of a different faith alone. It was the raison d’ etre of all persons displaced as a result of generational aspirations who migrated from one part of the country to another and had to deal with shifts in language, dress, food and weather conditions and remained at the receiving end of hierarchies of class, caste, religion and gender. Yet, Rakhshanda’s documentation of the everyday discomforts of belonging to a different faith and being treated differently thereof is an eye-opener.

I was unaware that the Jamia Nagar neighbourhood near Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi had no functioning MCD dispensary, the nearest government hospital was miles away, Fair Price Shops, Safal and Mother Dairy outlets for fruits, vegetables and milk were non-existent, or that delivery boys from nearby eateries, dry cleaners, chemists, grocers and florists would not provide delivery at doorsteps.

While everyday living can be isolating and traumatic due to the combined indifference of the State, civic authorities, insensitive landlords and fellow citizens, the continued demonisation of the Muslims in popular culture and films as smugglers, hoodlums or sinister dons, and the continuing stereotyping of Muslim men as debauched, chasing Hindu women, and Muslim women as inherently sly or cunning (as in Ranjhana and Lipstick Under my Burkha), have also been contributing factors.

It is bigots who speak through the language of power — poets and visionaries do not. It is necessary for us to absorb these narratives, revive them and reassert our faith in them. Our poetry and literature in diverse languages and faiths have spoken of collective communities and shared living; our myriad regional languages and dialects need to be revived and celebrated instead of being continually given short shrift.

It speaks poorly of us as a nation if democracy is only the brute, unthinking power of the mob, forever on the rampage against ideas, communities, shared festivities — disparaging of women’s freedoms and thoroughly disrespectful of difference.

Increasingly, in our public spaces, languages have been robbed of their contexts and culture and diminished to a functional and linear purpose. Literary and oral traditions have been replaced by an unvetted audio-visual exchange available on the internet and Whatsapp. This feeds in all manner of unverified hype and hysteria.

Read an interview with the author of the book Rakshanda Jalil

Meanwhile, filmmakers and actors, movers and shakers in this new world, get together to make banal films with banal narratives that caricature and make simplistic all that has inherent originality, or a complex value, overlooking ordinary rural and urban lives altogether. In the film Padmavat, for instance, Sanjay Leela Bhansali, the film’s director, has already erased both history and context from a fictional poem written in the 16th century, in pretty much the same way that he erased history from all of his previously opulent productions. Its lead hero, a Hindu, plays the role of a demonised Muslim tyrant. He speaks of the acting process as demanding a transformation of his decent personality into that of the savage and vicious Khilji; apparently, he could never identify with Khilji, though he played his part. Meanwhile, a bounty was placed on the lead heroine’s neck by certain aggressive casteist and sexist groups.

In real life, the villain and the heroine from tinsel town eventually marry, but before the film is released, rabid groups object to the insult directed at Rajput women, demanding that the heroine’s waist be digitally covered. Besides, they attacked and terrified children in a school bus, and burnt and damaged public vehicles and property. Bizarrely, in the 21st century, women offered to commit ‘jauhar’ should the film be released.

How did we even get here?

It speaks poorly of us as a nation if democracy is only the brute, unthinking power of the mob, forever on the rampage against ideas, communities, shared festivities — disparaging of women’s freedoms and thoroughly disrespectful of difference. Our detached, non-commital media report lynchings in different parts of the country and videos of the horrors inflicted on ordinary Indian citizens surface, but little is done to end this horror. Most do not even report the lynchings or other acts of organised and transparent atrocities. This is the new normal in India.

Have we lost our tongue after all and become a nation of passive viewers unable to distinguish film from real life?

Meanwhile, valued traditions, personages from the past and powerful institutions, continue to be bowdlerised. Truth be told, we may look like humans, but, truly, we are beginning to behave less and less like humans should.

The writer is Associate Professor, English Literature, Venkateswar College, Delhi University