If Mukesh had applied for audition at the All India Radio, he probably would have failed. Or, if he were lucky, perhaps got a B grade — the lowest grade awarded to artists based on the performance quality adjudged by a Committee of Eminent Musicians and Experts (B-High, A, and Top being the other grades).

At some places in the song, he may have been found to be be-sura, or, perhaps, out of beat. The Committee would have found his diction to be wanting in some parts. The judges would have found his range to be limited, his voice nasal. They would have discovered that he had no classical training and could not do an alaap — forget the alankars. He would not have ticked most boxes in the judges’ scoring sheet as laid down by the State-owned broadcaster. The judges’ hands would be tied.

But they would have gone home and felt very uneasy, very guilty. The singer may have been imperfect, may not have had the technique, but he had touched their hearts. They could feel the pathos in his voice, the sincerity in his rendition, the innate sadness in every word that was sung.

There was directness in his approach; there were no filters in his outpouring. His singing was primal, unadulterated, simple, and appealing to the soul.

At the audition, they had used their minds and failed him. At home, they were using their hearts, and would have passed him with flying colours.

A gem is a gem, polished or not.

To express tiredness and disappointment with society, a distinctive kind of voice is required. A rich baritone works great. If the voice has no frills and is sourced not from the lungs, but straight from the heart, it summons up something that is ethereal and soulful. If the voice can convey life’s truths with a feeling of longing and tenderness, it can move even an obstinate boulder. If the voice is filled with character, originality and straightforwardness, it can bring tears to the eye.

In the early 1920s, HMV had rejected SD Burman for his nasal twang. KL Saigal also met the same fate.

It is a good thing that Mukesh did not venture close to AIR but carved an independent path right from day one. In any case, since he started off as an actor-singer, radio was not on his ‘to-do’ list.

My own maternal uncle, the late Satish Bhatia, who retired as a Chief Producer (Light Music), AIR, and must have sat on many such auditions, himself used Mukesh when he composed music for V Shantaram’s ‘Boond Jo Ban Gay Moti’ (1967). The song, ‘Yeh Kaun Chitrakar Hai’, which became a huge hit, could not have been delivered by any of the AIR-empanelled singers with the same emotion and feeling that Mukesh brought to it.

My mother, Usha Bhatia, herself a radio artist, sang at a live show alongside Mukesh and Geeta Roy at Odeon Theatre in the early 1950s. So impressed was Mukesh with her singing, that he presented her a Saima Swiss watch, which she has still preserved as a prized memento.

To express tiredness and disappointment with society, a distinctive kind of voice is required. A rich baritone works great. If the voice has no frills and is sourced not from the lungs, but straight from the heart, it summons up something that is ethereal and soulful. If the voice can convey life’s truths with a feeling of longing and tenderness, it can move even an obstinate boulder. If the voice is filled with character, originality and straightforwardness, it can bring tears to the eye.

That would be Mukesh.

He communicated emotion — especially the sadder variant — in a way that was unparalleled. He conveyed the dard to his audience. He was a blues singer who wore a brown skin and sang in Hindi.

He was a singer who thoroughly internalized the words of the songs he sang, becoming the messenger of the poet. The simple packaging of the words ensured their optimal registration in the minds of the listeners. The simplicity may have been mocked by some, but it served the purpose of the song. He was truly a man of the masses.

Comparisons are odious, yet, to understand his impact, it is nevertheless necessary. Let us see how Mukesh (who was not even considered worthy of Padma Shri) stacks up against Bharat Ratna Lata Mangeshkar — the complete singer, the perfect nightingale — in twin or tandem songs (same or similar song sung by two different singers).

Decide for yourselves.

Take ‘Aa Laut Ke Aja Mere Meet’ (Rani Rupmati, 1957). Can you imagine any other singer doing justice to this song, Lata included?

In ‘Mujhko Is Raat Ki Tanhai Mein’ (Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere, 1960) — Mukesh wins with a massive public approbation. Then there are songs like — ‘Humne Tujhko Pyar Kiya Hai Jitna’ (Dulha Dulhan, 1964), ‘Jyot Se Jyot Jagate Chalo’ (Sant Gyaneshwar, 1964), ‘Jis Dil Mein Basa Tha Pyar Tera’ (Saheli, 1965), and so on. Of course, in some songs, the honours were even but never inferior— ‘Raat Aur Din Diya Jale’ (Raat Aur Din, 1967) and ‘Chandan Sa Badan’ (Saraswatichandra, 1968).

Let us see how Rafi compares with Mukesh. Consider ‘Saranga Teri Yaad Mein’ (Saranga, 1961). The composition of the song was such that only the ‘Emperor of Melancholy’ could do full justice to it. No other male singer, including Rafi in this case, could even come close. Many do not know that Rafi also rendered this song, but his version is relatively unknown.

Even Manna Dey could not best Mukesh’s heart-touching rendition of ‘Zindagi Khwaab Hai’ (Jaagte Raho, 1956). Mukesh invested the song with such intensity and emotion, and with such consummate ease – he did not even have to try – his voice was suffused with it by default. But Manna’s version, otherwise technically the best Hindi film singer, seemed contrived.

Forget twin songs. Even in films where he got only one song to sing, he normally outshone the other male songs. ‘Chal Ri Sajni’ – a background song in Bambai Ka Babu (1960) was a huge hit besting Rafi’s ‘Saathi Na Koi Manzil’. Mukesh got the song only because Kishore Kumar turned it down, since the song was not picturised on Dev Anand whose main voice in the film was Rafi.

SD Burman had many misgivings about entrusting the song to Mukesh. If the Mukesh recording turned out to be unsatisfactory, SD Burman had threatened to scrap the song. However, such was the spell cast by Mukesh, that the song was retained. The “not a good singer” (as SD Burman rated him) had weaved his magic.

In Bandini (1963), Mukesh was again summoned by SD Burman for the atmospheric number ‘O Jaane Waale Ho Sake Toh Laut Ke Aana’. SD Burman — the Bengali folksinger par excellence that he was – also sang ‘O Re Maajhi… O Re Maajhi’. But Mukesh eclipsed him in popularity with his rendition.

Salil Chowdhury wanted ‘Suhana Safar Aur Ye Mausam Haseen’ on Dilip Kumar in Madhumati (1958) to be sung by Hemant Kumar. Could Hemant Kumar have – even with the allure of temple bells in his voice — done a better job than Mukesh? You decide.

Dilip Kumar initially wanted Talat Mehmood for both ‘Suhana Safar’ and ‘Toote Hue Khawabon Ne’. Could Talat have delivered the goods? Rafi ultimately sang ‘Toote Hue Khawabon’. Yet, did Rafi’s ‘Toote Hue’ displace Mukesh’s ‘Suhana Safar’? You decide.

And there is no dearth of such instances, where just one song by Mukesh in a film, emerged on top.

It’s not that Mukesh was not aware of his limitations; nor was he averse to criticism. But he took it in his stride.

Sometimes, while singing ‘live’ with Lata, he would jocularly ask the audience whether they knew why Lata was the greatest singer — it was only because she had such an out-of-tune singing partner like him! And this from a singer who had rendered absolute top-drawer duets with Lata like ‘Bade Armaano Se Rakha Hai Kadam’ (Malhar, 1951),‘Dekho Mausam Kya Bahaar Hai’ (Opera House, 1961), ‘Dil Tadap Tadap Ke Keh Raha Hai’ (Madhumati, 1958), ‘Sawan Ka Mahina’ (Milan,1967), ‘Phool Tumhe Bheja Hai’ (Saraswatichandra, 1968), ‘Ek Pyaar Ka Naghma Hai’ (Shor, 1972), ‘Kabhi Kabhi Mere Dil Mein’ (Kabhi Kabhie, 1976), and so many others.

However, to assign only the melancholy slot to Mukesh would not be correct. He could also belt out light numbers with consummate ease. Songs like ‘Ruk Jaa O Jaane Wali Ruk Jaa’(Kanhaiya, 1959), ‘Aasman Pe Hai Khuda’ (Phir Subah Hogi, 1958), ‘Itna Husn Pe Guroor Na Kijiye’ (Mohabbat Isko Kehte Hain, 1964), and others are a testimony to this facet of his oeuvre.

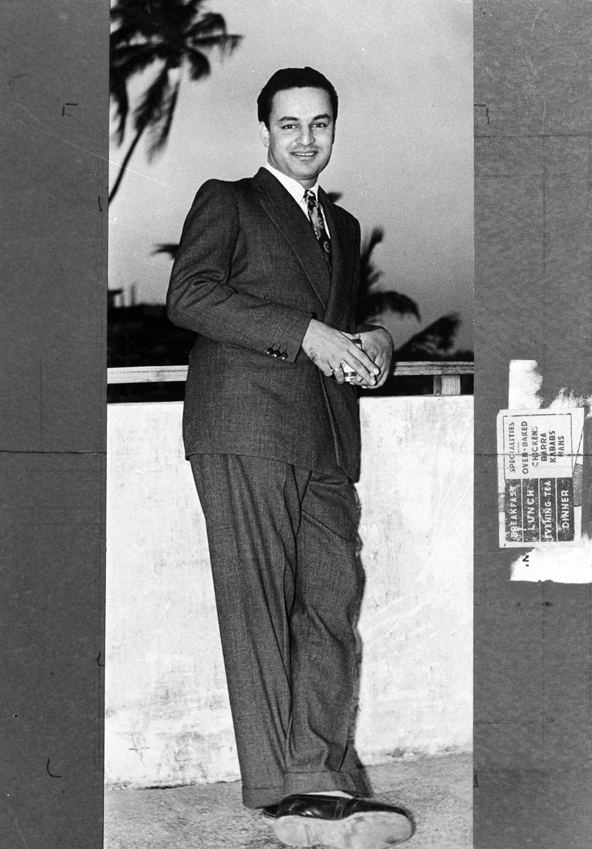

Born in Delhi on July 22, 1923, Mukesh left for Bombay soon after finishing matriculation to try his hand at acting. At the age of 18, he made his film debut as a hero opposite Nalini Jaywant in Ranjit Movietone’s Nirdosh (1941). A strong recommendation from his relative, noted actor Motilal, gave Mukesh this opportunity. He also sang his first movie song, ‘Dil Hi Bujha Hua Ho Toh’, composed by Ashok Ghosh.

Both the movie and the song sank without any trace. His other acting ventures also met with the same fate. Hence, acting had to be given up and full-time playback singing had to be taken up to keep body and soul together.

His first singing success came in Paheli Nazar (1945) under the baton of Anil Biswas. Mukesh wanted to be the second KL Saigal. So, Anil Biswas cast him in the mould of KL Saigal through the poignant ‘Dil Jalta Hai to Jalne De’. The song was a massive hit.

Who could have known that a slap could change the destiny of a man and that of the film industry? Indeed, without that slap, Mukesh would not have been the Mukesh we know.

During the rehearsal, Mukesh could not grasp the complexities of the song. When he kept failing, Anil Biswas told him that he would sing the song himself. Reportedly, Mukesh complained to some people that if composers started singing their own songs, what would happen to singers?

Let us see how Rafi compares with Mukesh. Consider ‘Saranga Teri Yaad Mein’ (Saranga, 1961). The composition of the song was such that only the ‘Emperor of Melancholy’ could do full justice to it. No other male singer, including Rafi in this case, could even come close. Many do not know that Rafi also rendered this song, but his version is relatively unknown.

Anil Biswas heard about it and agreed to let Mukesh sing. On the day of the recording, the musicians had finished and Mukesh had not arrived. Anil Biswas got very upset. He was informed that Mukesh was drinking at a bar because he was very nervous and felt that he will not be able to sing.

Anil Biswas went to the bar and picked him up by the collar. He did his best to shake him out of the haze by putting his head under the tap and giving him a glass of black coffee. When a sobered up Mukesh expressed his inability to bring pain into his singing, Anil Biswas reportedly slapped him hard and asked him to bring that very pain into the recording room.

Mukesh could have objected and walked out of the song, and, effectively, the film industry. But he chose not to and never held a grudge against Anil Biswas for the rest of his life.

Anil Biswas told Mukesh that they had both proved that they could do a KL Saigal. Now they had to prove that Mukesh was Mukesh, the authentic product, not just an imitation of KLSaigal. Instead, he advised him to develop his own style.

Anil Biswas’ Anokha Pyar (1948) and Naushad’s Mela (1948) and Andaz (1949) presented Mukesh in his own original style as Dilip Kumar’s voice. Songs like ‘Gaaye Ja Geet Milan Ke’, ‘Dharti Ko Aakash Pukare’, ‘Main Bhanwara Tu Hai Phool’ and ‘Mera Dil Todne Wale’ from Mela; ‘Jhoom Jhoom Ke Naacho Aaj’, ‘Tu Kahe Agar’, ‘Toote Na Dil Toote Na’, and ‘Hum Aaj Kahin Dil Kho Baithe’ from Andaz became a rage.

Naushad too had a role to play in the transformation. Mukesh had a drinking problem in his initial years as a singer. One day Naushad caught him drunk during the daytime and told him that he had already proved with ‘Dil Jalta Hai’ that he could do a KL Saigal. What was it that he was now trying to prove – that he could out-do Saigal in drinking too?

Mukesh was in tears. Naushad demonstrated to him that he had a voice identifiably his own, which would prove his vocal credentials.

The association with Dilip Kumar was short-lived as Dilip Kumar switched over first to Talat and then to Rafi as his playback.

However, you cannot keep a good talent down. Raj Kapoor stepped in. In Aag (1948), Mukesh sang ‘Zinda Hoon Is Tarah’ for Raj Kapoor and a life-long partnership came into existence. Mukesh’s voice was tailor-made for Raj Kapoor’s screen image of a tragicomic tramp, prompting Raj Kapoor to state that he was just a body, and Mukesh was his soul.

The role of Raj Kapoor in making Mukesh a star was huge. Raj played the role of an impoverished simpleton who only Mukesh could best articulate. In post- Independence India, where innocence clashed with the harsh hurly-burly of reality, the resultant despondency required a voice and who better than Mukesh to convey pain and angst, yet never losing hope.

Backed with Shankar-Jaikishan’s outstanding music, the message went through. The songs, right from Barsaat (1949) to Mera Naam Joker (1970) are many and well-known and do not require any detailing.

Kalyanji- Anandji were also firmly in Mukesh’s corner and served the listeners some delectable numbers such ‘Chhalia Mera Naam’, ‘Mere Toote Hue Dil Se’ , ‘Dum Dum Diga Diga’ (Chhalia, 1960 ), ‘Mujhko Is Raat Ki Tanhai Mein’ (Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere, 1960), ‘Hum Chhod Chale Hain Mehfil Ko’ (Ji Chahta Hai, 1964); ‘Main To Ek Khwab Hoon’, ‘Chand Si Mehbooba Ho’ (Himalaya Ki God Mein, 1965) ; ‘Waqt Karta Jo Wafaa’ (Dil Ne Pukara, 1967) , ‘Deewanon Se Yeh Mat Poochho’ (Upkar, 1967), ‘Chandi Ki Deewar’ (Vishwas, 1969) , ‘Koi Jab Tumhara Hriday Tod De’ (Purab Aur Paschim, 1970 ), and so many others.

Laxmikant -Pyarelal also had Mukesh’s back. Consider some of the songs — ‘Saawan Ka Mahina’ and ‘Ram Kare Aisa Ho Jaaye’ (Milan, 1967), ‘Ek Pyar Ka Naghma Hai’ (Shor, 1972), ‘Mai Na Bhoolunga’ (Roti, Kapada Aur Makaan, 1974).

Similarly, Roshan also swore by him and produced outstanding songs: ‘Tum Agar Mujhko Na Chaaho Toh’ (Dil Hi to Hai, 1963), ‘Baharon Ne Mera Chaman’ (Devar, 1966), ‘Ohre Taal Mile Nadi Ke Jal Mein’ (Anokhi Raat (1968).

Likewise, with Salil Chowdhury, Mukesh sang such immortal songs: ‘Maine Tere Liye Hi Saat Rang Ke’ and ‘Kahin Door Jab Din Dhal Jaaye’ (Anand, 1971), and ‘Kayee Baar Yoon Hi Dekha Hai’ (Rajnigandha, 1974).

Mukesh was a creature of the laid-back, idealistic, and empathetic times of the 1950s and 60s. Mukesh helped shape these times. But with Hindi film themes changing tack from the mid-70s, with social themes being supplanted by revenge and gore, with dard not the flavour of the season, with simpletons being classed as losers, Mukesh’s role began diminishing, though even the few songs he did continued to be chartbusters.

He died at a young age of 53, no age to depart, during a tour of the USA in 1976 along with Lata.

Singers like Mukesh are rare. His output was miniscule compared to his peers. But each song is outstanding.

Curating the ‘Best of Mukesh’ is no problem. One just needs to dip one’s hand in his musical till and select whatever is grabbed by the fist.

On his 98th birth anniversary today — July 22 — we remember a singer who left an indelible imprint on the national consciousness by his charismatic voice, his simplicity in singing, his abiding humility, his emotional depth, and his art of communication.

He may have lacked in technique but not in his best impulses. His vulnerability, his imperfections, made him accessible to the listener. His sincerity of spirit aimed straight at the heart.

Sab kuchh seekha usne, na seekhi hoshiyari, sach hai duniyawalo ki woh tha anari.

That is why Mukesh will live on forever.