Editor’s Note

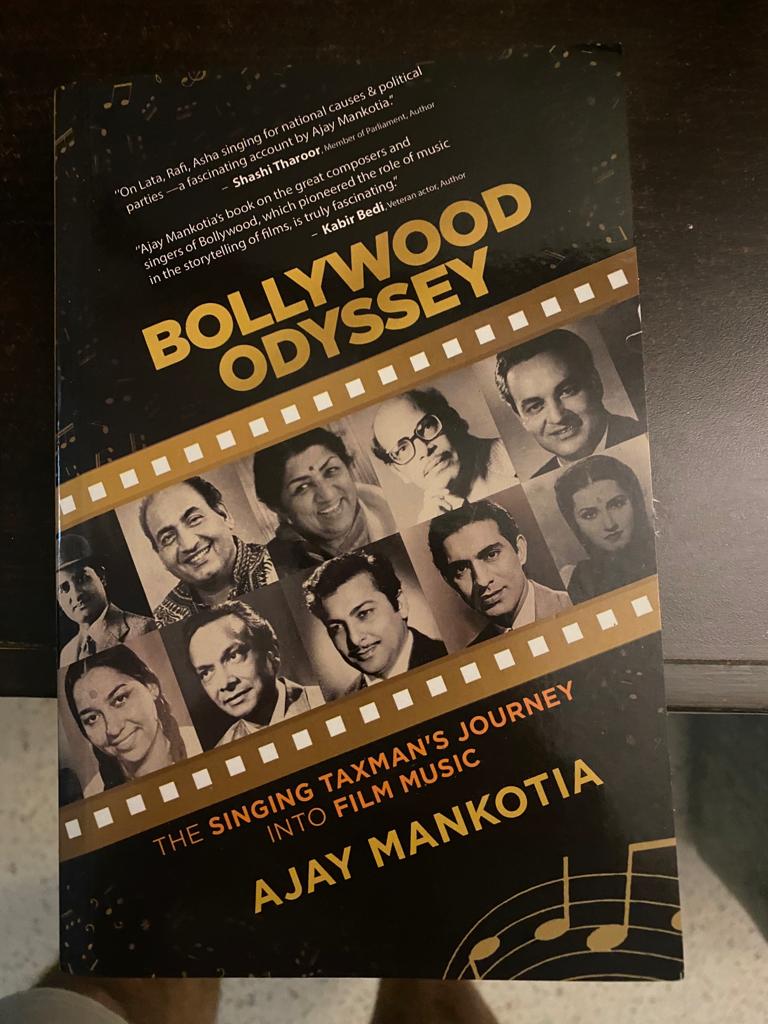

This excerpt is from Ajay Mankotia’s latest book titled, “Bollywood Odyssey”. Published by Delhi based publishing house, Readomania, the book provides a unique perspective to Bollywood that has not been explored in the past. A former bureaucrat, Mankotia, has few peers when it comes to understanding Bollywood and its music. Readers of Hardnews may have got a sense of his knowledge of film music, but for others this book would open a new world of unknown nuances of how great composers crafted their music around famous lyrics. There is so much more that they would get to know about Indian cinema as they read this book.- Editor

–

By Ajay Mankotia

Amitabh Bachchan’s breakout film, Zanjeer (1973), has a duet ‘Deewaane Hain Deewano Ko Na Ghar Chaahiye, Muhabbat Bhari Ik Nazar Chaahiye’. But the song is not sung on screen by Amitabh and Jaya Bhaduri. Amitabh’s role in the film is too serious—of an angry young man—to warrant a song and dance routine, though Jaya has no such issues, having sung ‘Chakku Chhuriyan Tez Kara Lo’ earlier in the film. So how is the budding romance between the two protagonists to be depicted on screen, when the male lead has been forbidden to do so by the film’s script? Enter the buskers Gulshan Bawra (playing the harmonium), also the film’s lyricist, and a minor actress Sanjana. They sing with gay abandon on behalf of Amitabh and Jaya, expressing the emotions raging inside the hero and heroine, as they watch the street song from Amitabh’s house while simultaneously exchanging coy glances at each other.

Incidentally, singer Mohammad Rafi had been fasting and was a bit irritable during the song’s recording. One ‘take’ of the song had been okayed by the music directors Kalyanji-Anandji, but co-singer Lata Mangeshkar wanted a retake. Uncharacteristically, Rafi refused. Gulshan Bawra followed him out of the studio and told him that he was going to enact this song on screen. Rafi came back and gave two ‘takes’ and sang it in a way that suited Gulshan Bawra’s persona.

A year later, in Majboor (1974), Amitabh would step out of the room and try to placate Parveen Babi through the good offices of the beach buskers (in the voice of Rafi and Asha Bhosle)— harmonium and all—in ‘Roothe Rab Ko Manana Aasaan Hai, Roothe Yaar Ko Manana Mushqil Hai’.

Buskers in India, like their Western counterparts in markets, metros, pavements, street corners, beaches, waterfronts, railway stations, entertain the public. But unlike the western counterparts, they also play a role in films by vicariously conveying the feelings of the actors who cannot or will not do it themselves. These buskers play the role of their surrogate—they deputize for them to ensure that film story continues its journey

Hindi films are replete with this fascinating cinematic device.

A similar song was enacted in CID (1956) with a harmonium-slung Shyam Kapoor (Rafi) and flautist Sheila Vaz (Shamshad Begum), singing ‘Leke Pehla Pehla Pyar’ on behalf of Dev Anand and Shakila. The debonair, and clearly love-struck, Dev would have done the honours himself, but his love-interest is in no mood. Enter the buskers as the outsourced service providers. The lady dancer confronts Shakila—“Mukhde pey daley hue zulfon ki badli, chali balkhati kahan ruk ja o pagli”. In the later stanza, she continues—“Dekha aisa mantar maar, akhir hogi teri haar, jadunagri se aaya hai koi jadugar”. All this while, Dev walks behind Shakila, egging the buskers on. The experiment works and the lady eventually, whilst at her house, melts. The buskers having done their job and left the screen, she (in the voice of Asha Bhosle) laments—“Uski deewani haai kahun kaise ho gayi, jadugar chala gaya main toh yahan kho gayi”.

The harmonium again appears (street-singers cannot do without it) in the song ‘Bichhde Hue Milenge Phir, Kismet Ne Gar Mila Diya’ (Post Box 999, 1958). There is a dholak player too, and a female dancer. Shakila (unamused) and Sunil Dutt (smiling) are amongst the audience. The song not only takes care of them, but Leela Chitnis too, craning her neck—the song articulating her conviction that those separated would meet again one day.

Sheila Vaz reprises her role as a busker in ‘Jab Hum Tum Dono Razi, Toh Kya Karega Qazi’ in Bade Sarkar (1957). The ubiquitous harmonium, along with the dholak, is in attendance. Kishore Sahu and Kamini Kaushal have had a lover’s tiff. Vaz (in the voice of Asha) proclaims—“Kyun duniya ke pichhe bhage, kuchh nahin duniya dil ke aage, dekh nazara pakad ke hath humara, samajh le dil ka ishara, jamaa le rang zaraa”.

In Dil Apna Aur Preet Parai (1960), the minor actor Raj Kishore wields the guitar, while a female extra plays the harmonium, and a male extra, the dholak. Raj Kishore (in Rafi’s voice) sings ‘Jaane Kahan Gayi, Dil Mera Ley Gayi Woh’, echoing Raj Kumar’s anguish at his doomed love affair with Meena Kumari (all works out well in the end though). A dejected Raj Kumar, sitting on a rock next to the sea, could not have been expected to sing the song of separation; it did not suit his character. Enter the trio and sing on his behalf.

This phenomenon is as old as the films. As long back as in 1937, Izzat had a song—‘Prem Dor Mein Baandh Hume, Kit Chale Gaye Girdhari’ sung by minor actors in the voice of Ashok Kumar and Devika Rani (music by Saraswati Devi) for Devika Rani pining for Ashok Kumar. For a brief period during the song, she dreams of herself singing it with Ashok Kumar. Even the actress credited with the longest kiss in Hindi films (in Karma, 1933) could be coy and let others emote for her!

And the list goes on. ‘Mohabbat Ka Haath, Jawani Ka Palla’ in Howrah Bridge (1958) on Ashok Kumar and Madhubala; ‘Ek Bewafa Se Pyar Kiya’ in Awara (1951) on Nargis; ‘Nain Khoye Khoye’ in Munimji (1955) on Dev Anand and Nalini Jaywant; ‘Nigahon Ka Ishara Hai’ in Night Club (1958) on Ashok Kumar and Kamini Kaushal; ‘Dhalti Jaaye Raat, Kehde Dil Ki Baat’ in Razia Sultana (1961) on Jairaj and Nirupa Roy.

It is not only the buskers who put to song the emotions heaving inside the hearts of the main actors. There is another equally important category—the boatman. He not only plies his trade in ferrying people across the river, but also creates the atmosphere, the mood, the ambience by singing (usually) a philosophical ditty. And, sometimes gives voice to the innermost feelings of the main cast.

The iconic ‘Sun Mere Bandhu Re’ in Sujata (1959) is one such song. If Hemant Kumar is considered the voice of God, SD Burman, who also composed the song, is the ghost voice of all Bengali boatmen. His voice was plaintive, serene, slow and melodious. In this song, picturized on the romancing Sunil Dutt and Nutan, the song evocatively captures their mutual feelings for each other.