By Anjali Chauhan, Delhi University in New Delhi

The loopholes in labour laws will need to be plugged if gig workers are ever to get a fair deal.

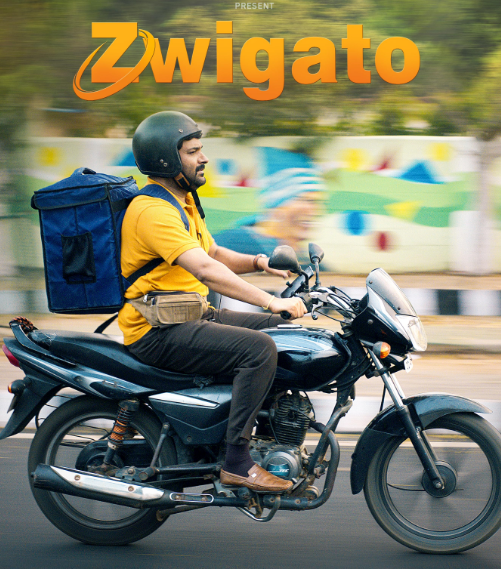

In September 2022, the highly anticipated Hindi-language film ‘Zwigato‘ debuted at the Toronto International Film Festival, shedding light on the lives of food delivery workers in India. Directed by Nandita Das and co-written by Samir Patil, the movie gained attention for delving into the darker aspects of India’s gig economy.

It narrates the story of Manas Singh Mahto, a fictional delivery rider in Bhubaneswar, depicting the challenges faced by Indian gig workers.

Portrayed by comedian Kapil Sharma, Mahto endeavours to meet daily delivery targets to secure incentives, grappling with obstacles such as dealing with restaurant proprietors and confronting societal biases based on caste and religion inherent in the profession. However, the film merely scratched the surface of the underlying issue.

According to the ‘India’s Booming Gig and Platform Economy’ report released by the National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) in 2022, there were 7.7 million people employed in the gig economy in the fiscal year 2020-21. That number is expected to soar to 23.5 million workers by 2029-30.

The sheer extent of gig worker numbers shows the urgency of discussing and dealing with the issue.

In both Indian and global contexts, labour laws generally do not cover or regulate food delivery or gig workers broadly associated with digital platforms. This gap exists due to the unique nature of their work relationships, which do not fit the conventional employer-employee model.

Digital platform aggregators classify gig workers as partners rather than formal employees. This classification enables companies to sidestep compliance with labour regulations, thereby minimising labour costs and obligations.

By designating these workers as partners rather than employees, companies evade responsibilities such as providing regular wages and benefits. Instead, food delivery workers’ compensation is primarily based on delivery charges and incentives.

This distinction allows companies to bypass certain labour law provisions, leaving workers without the protections and entitlements typically afforded to traditional employees.

This loophole in classification hinders the extension of necessary labour safeguards to gig workers, creating challenges in ensuring fair and secure working conditions within the gig economy.

Under these circumstances, unionisation has become both necessary and difficult. One such union which is extending its efforts to unionise gig workers is the App Workers’ Unity Union which is affiliated with All India Central Council of Trade Unions (AICCTU).

The union has worked extensively in the Delhi NCR area and led the Blinkit workers’ series of protests which broke out when the company arbitrarily rolled out its new payout structure for delivery workers, under which the minimum payout per delivery was reduced to Rs15 (USD$0.18) per delivery.

Apoorva, coordinator of the App Workers’ Unity Union spoke about the difficulties the union faces to organise workers under the new scheme of gig work.

“The big claims of flexibility and autonomy of gig work are false. Most of the workers work more than 12 hours per day. Sometimes it even goes up to 20 hours. They are forced to work for long by the team leaders and threatened with their IDs being blocked if they do not abide,” Apoorva said.

“Such a pressurised and mobile nature of work adds challenge for unionisation which has already been experiencing setbacks for the last decade.

“We have constantly kept going to the stores and stops where the riders wait for orders to engage with them. But often we are not able to create sustained dialogue with them as every time we reach a store, new workers will be there and older ones might have shifted.

“However, when we start talking about their problems and sufferings, they tend to listen and contribute to the conversations. Additionally, as the means of this form of work is digital, we have to keep pace with it too. So we have been trying to create a strong online presence through social media like Instagram and Facebook. We also have a WhatsApp group.”

The union is also distributing a booklet to gig workers across Delhi which addresses some common questions workers have regarding the union. Some of the questions addressed were: Are all workers happy with their work? Why is our situation so bad? How to take membership? How to form a union in such difficult circumstances? and what is the vision of the union?

The December 2021 report titled ‘Behind the Veils of Algorithms: Invisible workers; A Report on the workers in the gig economy’ by the Peoples Union for Democratic Rights presents another pivotal analysis of the gig economy.

Contrary to the common perception that gig work serves as a supplementary income for individuals during their leisure hours from a primary job, for many gig workers interviewed, this type of work constitutes their primary source of livelihood.

Unlike freelancers, who often have some degree of autonomy, gig workers lack control over setting fares or fees for the services they provide. Instead, these decisions are made solely by the company they work for.

The report reveals that companies unilaterally decide the compensation for workers, which is often influenced by consumer demand and the number of available workers for a specific task at any given time.

This system results in an algorithm-driven control mechanism where workers have minimal say in their working conditions, contradicting the notion of autonomous and independent entrepreneurship within the gig economy.

Amid such testing times, neither the government nor the companies are willing to even have a dialogue regarding the hardships this form of work has brought.

The companies are continuously reducing the pay rates and incentives, and the government is not responding to the complaints put collectively by the unions and workers for the same.

App Workers’ Unity Union sent a memorandum of demands to the Union Labour Minister on 27 April, 2023, demanding all app-based employees be granted the status of permanent worker of their company concerned, eight hours of work per day to be fixed with a guaranteed wage of at least Rs. 26,000 (USD$315) per month and ensure social security through necessary laws.

Nothing happened.

Another pertinent issue the union raised was during the Delhi floods. A memorandum was sent to the Delhi government to alert it to the dangerous conditions delivery workers faced while working from home.

The union demanded that all app-workers making deliveries in flood-affected areas should be paid Rs 15,000 (USD$180) as a ‘risk allowance’ and that any app-employees unable to work due to floods should be given a special allowance of Rs 1000 (USD$12) per day. Again, there was no response by the government.

The velocity with which gig work is taking over the global work landscape is unfathomable. It has not only brought new challenges for unions but has also taken the world back to the 1920s when workers put up a united front to demand an eight-hour workday.

To tackle the same, the App Workers’ Unity Union is consistently putting effort into forming a collective front and bringing major trade unions under the same cause and banner to give a national call against the exploitation of gig workers.

Anjali Chauhan is a doctoral student at the Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, India.

This article is part of a Special Report on the ‘sian Gig Economy, produced in collaboration with the Asian Research Centre – University of Indonesia.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.