by Prema Sridevi

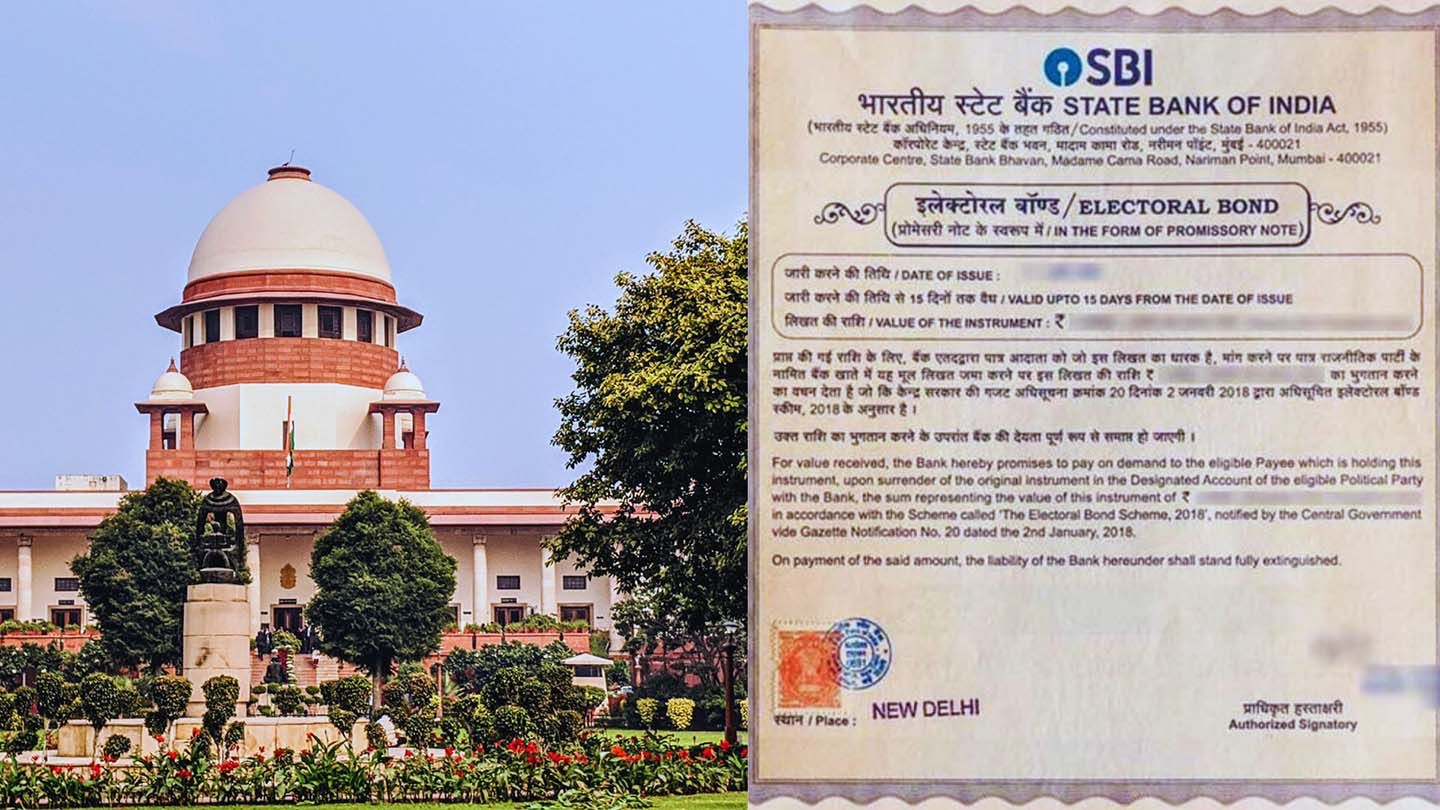

Just before the 2024 general elections, the Supreme Court (SC) delivered a landmark verdict, striking down the Electoral Bonds (EB) scheme calling it “unconstitutional”. Although the financial repercussions of this ruling on the upcoming elections might not be significant—given that many political parties, especially the BJP, one of the primary beneficiaries, have already amassed thousands of crores for use in the forthcoming elections—the verdict still stands as a victory for democracy in India.

The SC verdict has unsettled numerous beneficiary political parties. Although the judgement arrived later than desired, it’s a case of better late than never. Recognising the significance and impact of this landmark decision, it’s hard not to reflect on how certain constitutional bodies in India stood by silently for years, as political parties pocketed vast wealth through the EB scheme. Even the Supreme Court, the highest judicial authority, found itself constrained for years as political parties continuously enriched their coffers with funds from anonymous donors.

The central government exerted its full authority to amend, omit, add, and create new regulations to ensure the electoral bond scheme’s passage, safeguarding donor anonymity while compromising the rights of voters. Many revisions were made, such as altering Section 29C of the Representation of the People Act via the Finance Act 2017, which exempted political parties from disclosing financial contributions received through electoral bonds. Section 182 of the Companies Act 2013 was also modified, allowing private companies to donate any amount to political parties, directly or indirectly. Furthermore, the Finance Act 2017’s amendment to Section 182 of the Companies Act removed the cap on the maximum contribution a company could make to a political party. Political parties also benefited from special privileges concerning voluntary contributions under Sections 13A and 13B of the Income Act, 1961. Despite the Supreme Court’s latest decision to strike down these controversial provisions, the way the government has manipulated regulations shows how government actions can be tailored to benefit their own interests.

Many questions emerge when considering the Supreme Court’s decision to label the electoral bond scheme as ‘unconstitutional’. The court’s use of ‘unconstitutional’ to describe the scheme prompts a critical reflection: if state and general elections were contested with funds obtained through such unconstitutional means, what does that imply about the legitimacy of those election outcomes? Moreover, it prompts a reflection on whether governments elected through these means possess the ethical standing to continue in power. The electoral bond scheme undermines the connection between elections and the principle of representative democracy, as it predisposes elected officials to prioritise the interests of their contributors over those of the voters.

What is also noteworthy is the way the centre through the Attorney General of India defended the Electoral Bond scheme in the Supreme Court. The government stated that the citizens do not have a general right to know regarding the funding of political parties. And not just the citizens, the government very brazenly told the SC that even the apex court did not have the right to look at political party funding and that it should be best left to the legislature.

As we evaluate the recent Supreme Court ruling, the role of the Election Commission of India (ECI) in this entire process cannot be overlooked. The ECI, the constitutional body tasked with conducting free and fair elections in the country, faces scrutiny: Has it fulfilled its duty? On 26 May 2017, the ECI expressed concerns to the Ministry of Law and Justice, stating that amendments to the IT Act, RPA, and Companies Act introduced by the Finance Act 2017 would severely impact the transparency of political funding. The ECI warned that unlimited corporate funding could increase the use of black money for political funding through shell companies. On 13 April 2019, the Supreme Court mandated all political parties to disclose the details of contributions received via electoral bonds to the ECI in a sealed envelope. Yet, nearly five years later, numerous political parties have still not complied, and the Election Commission of India hasn’t been able to do much. On the contrary, the counsel for the ECI told the SC that the ECI had only collected information on the political donations made in 2019 because a reading of the interim order indicates that the direction of the court was only limited to contributions made in that year. In reality, the interim order explicitly states that all political parties are required to submit the details of contributions received through electoral bonds to the ECI. At no point did the court specify in its order that this directive was limited to 2019 alone.

Transparency activist Commodore Lokesh Batra, dedicated to promoting electoral transparency, has filed multiple RTIs with the election commission seeking details on the electoral bond scheme. Last year, he submitted another RTI to the ECI, requesting a list of political parties that had complied with the Commission’s directive to submit details of Electoral Bonds in sealed covers. However, the ECI refused to disclose this information. In a conversation with me, Commodore Batra expressed his frustration, noting that such fundamental information was withheld by the ECI without proper justification. “The election commission cited Section-8(1)(b) of the RTI Act for its refusal, which pertains to information explicitly prohibited from publication by any court or whose disclosure might constitute contempt of court. I challenged this refusal through an appeal, pointing out that the Supreme Court had not imposed any ban on the publication of such information. What should have been readily available and transparent following the 2019 order of the apex court has now been shrouded in opacity. The ECI appears to be concealing information without presenting sound reasons for refusal to share even such basic information.”

While the ECI has not been proactive in making political parties accountable to the public so that free and fair elections can be conducted, what is even more mind boggling are the numbers. The figures related to electoral bonds for the fiscal year 2023-24 up until January 2024 are staggering, totaling ₹45,09,51,22,000. To put this into perspective, that’s ₹4509 crores, 51 lakhs, and 22 thousand. It’s important to note that this only covers a 10-month span. The increase from the previous year is astonishing; in the fiscal year 2022-23, the total was ₹28,00,36,01,000, which breaks down to ₹2800 crores, 36 lakhs, and one thousand rupees. The BJP has been the recipient of the majority of all contributions made through electoral bonds. Further scrutiny of the data shows that ninety-four percent of these funds were donated in one crore denominations. Moreover, the proportion of income from unidentified sources for national parties escalated from 66% in the period from 2014-15 to 2016-17, to 72% between 2018-19 and 2021-22. Specifically, from 2019-20 to 2021-22, income from electoral bonds constituted 81% of the total undisclosed income of national parties. This trend starkly shows the growing reliance on political funding from anonymous sources, effectively keeping the citizens in the dark and undermining the very foundations of our democracy.

In what can be called as the biggest triumph for the citizens of India, the Supreme Court’s recent ruling mandates the State Bank of India (SBI) to disclose complete details of all electoral bonds purchased. This includes the date of each bond’s purchase, the identity of the purchaser, and the denomination of the purchased bond. Additionally, the Election Commission of India is instructed to make this information publicly available on its official website by March 13, 2024. This directive brings the public closer to uncovering the identities of anonymous donors, revealing who gave what, when, and how. We may also get to know the biggest question: why these donations were made as the names of donors and the corresponding timelines of donations could serve as tip-offs and be a catalyst for journalists to investigate stories related to quid pro quo deals between corporates and respective state governments or the central government.

Political contributions made in return for favours falls under the category of money laundering under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. The Financial Action Task Force states that its member states have a duty to oversee and prevent any form of money laundering that involves political party contributions. Moreover, Article 7(3) of the United Nations Convention against Corruption, 2003 mandates that signatory nations, including India, must enhance the transparency of political financing for both candidates and parties. Then, the undeniable fact is that this kind of blatant money laundering, which kept the public in the dark, was carried out by political parties for many years, as some institutions watched on in muted silence. In the name of curbing black money, the biggest con was unleashed on democracy and the people of our country. The Supreme Court has finally put a full stop to this. But is the fight really over?

Prof. Jagdeep S Chhokar, Founding Member and Trustee of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), which is among the petitioners in the Supreme Court, cleared the air, “We are very pleasantly surprised by the Supreme Court’s verdict. This ruling is a step towards reinstating the public’s trust in democracy, the rule of law, and the Supreme Court itself. However, the powerful beneficiaries might resort to filing a review petition in the court, or we may encounter other kinds of obstacles. The fight is not over”.

The Supreme Court has laid the foundation for reform with its verdict, though arriving late. Yet, the real battle begins now. Until constitutional bodies and institutions in the country act independently and firmly oppose such blatant corruption, the government will continue to devise new methods for institutionalising corruption, just like the electoral bond scheme. What India requires at this juncture is institutional accountability and independence. We need institutions that do not become pawns in the hands of the governing powers. A strong foundation has been laid through the verdict but the battle is far from over.