Hathras, UP: The posters of Baba Narayan Sakar Hari a.k.a Bhole Baba, whose satsang caused a stampede in Pulria village in Hathras district killing over 120 people on July 2, stand unbesmirched– swaying in the gentle post-rain breeze, two days after the mayhem. The bamboo scaffolding with a stark blue-cyan striped canopy at the center of the event site looks like a shrine installed in memory of the deceased.

The field soaked by standing water due to incessant rain is dotted with small and big feet-shaped puddles. Empty packets of chips and chocolate wrappers litter the ground, creating an unsettling illusion of a family picnic where children enjoy their favorite treats. The trail of foot marks and chappals of those caught in the stampede continues for kilometers to the nearest village – Gadhiya, Iqbalpur of Sikandrarao Panchayat.

The residents here still haven’t overcome the shock of what they had witnessed so up and close.

“This event has been happening for 12 years. This year the crowd was huge and the event took place with very little police protection” said Shailendra Kumar, a resident of the village and an eyewitness.

Shailendra Kumar and others in his village witnessed the chronology of events that turned a religious congregation into a medical emergency in a district with bare minimum medical facilities and almost zero emergency preparedness.

“Things had started going wrong since afternoon. People tumbled over each other, mostly women and children from the Jatav community. We tried calling the ambulance but initially got no response. Within an hour and a half around five ambulances arrived. But due to lack of police presence, baba’s sevadars took over the road and hindered the movement of the ambulance, delaying the rescue process.” he adds.

He recalls how even when people were falling unconscious the sevadars of Baba Bhole kept on insisting that they all would be revived by the magical powers of the Godman, discouraging them from seeking administrative intervention.

Debris of bodies, under-staffed medical facilities

“The first bodies to arrive were those of three children. We were told more on their way, and then it didn’t stop.” says the Head Nurse at the Trauma Centre at the Sikandarau Community Health Centre.

This 30-bed medical facility, which is supposed to cater to the needs of 20,000 residents, is the only trauma center in Hathras. The trauma center has one doctor and five other nursing staff. This tiny place, about 6 kilometres away from the stampede site was the first stop where the dead and the injured were brought. To say they were ill-equipped to handle the casualty load would be a gross understatement.

“Out of the 96 bodies we handled, we could revive only two.” There were no stretchers to accommodate the bodies and complaints of lack of oxygen masks.

Addressing reports of a lack of oxygen masks, she adds, “We provided oxygen, but there were hardly any injured people; most were brought in dead. There was no possibility of reviving them.”

Handling the sheer number of bodies was a major challenge. Every bed in the facility held a pile of lifeless bodies. “No one could have anticipated this. We certainly ran short of resources, but we did our best. Our in-charge brought in many additional doctors to manage the emergency,” she says.

“We worked until 11 o’clock when all the bodies were sent for autopsies to different district hospitals in Kasganj, Aligarh, Hathras, and Etah. The injured were given first aid and transferred to other hospitals,” she added.

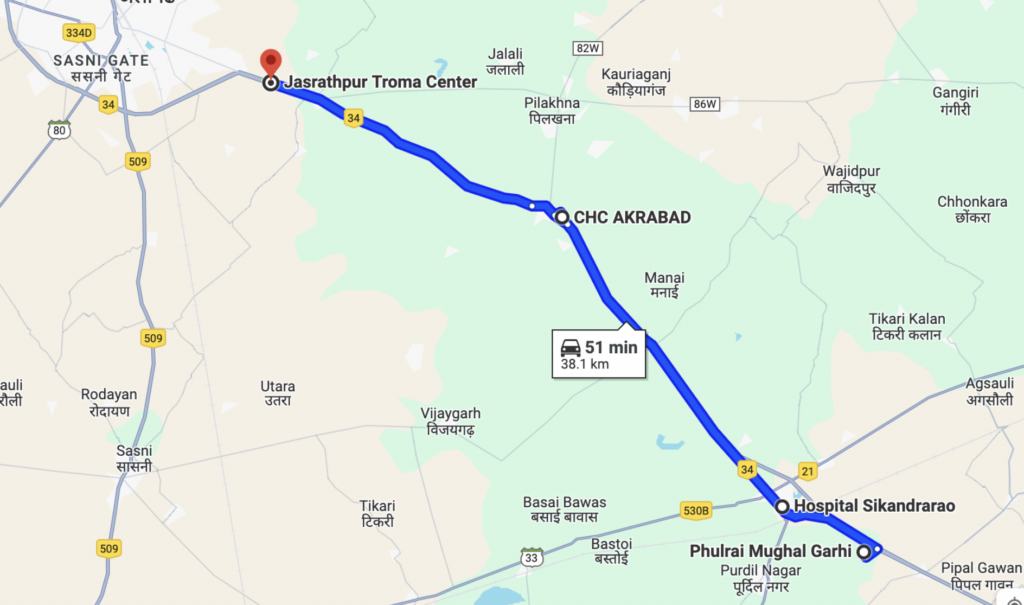

The medical staff here feel a pressing need for more such facilities in the vicinity. Interestingly, half an hour drive apart, on the border of Aligarh and Hathras at Jasrathpur, we discovered an almost-defunct trauma center. This practically was the second nearest trauma center to the incident. It is located on NH 34.

We found the facility staffed by only four people, including the shift head, a newly hired contract worker, who was relaxing at his desk. The two women claiming to be nurses were lying on beds, and clothes were hanging to dry on the IV stands.

We asked if the facility was used for the medical emergency on July 2nd, to which they replied in the negative. “We aren’t fully equipped to handle critical cases,” the doctor admitted.

Trauma centers are the primary responders in emergencies involving a high number of casualties – be it a road accident or an unforeseen event like the 2nd July stampede.

On paper, Uttar Pradesh currently has 36 public trauma centers, strategically located near highways, to provide specialist care within the crucial “golden hour” for road accident victims. Out of these 28 lack specialist doctors, hindering their ability to handle critical cases.

The Chief Medical Officer of both Hathras and Aligarh were contacted for their comments on the matter, but they refused to give us an appointment.

As per data released by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highway (MoRTH), even though Tamil Nadu has the highest number of road accidents, Uttar Pradesh accounts for the highest number of fatalities, which explains the inefficient functioning of the trauma centres.

It is not uncommon to see defunct and underutilized primary healthcare facilities in Uttar Pradesh. In fact, as per the 2021-22 rural health statistics report, Uttar Pradesh is one of the worst-performing states when it comes to staff shortages.

The state experiences an acute shortage of healthcare workers, including specialists, radiologists, lab technicians, and nursing staff. So even when facilities exist, there’s hardly anyone to operate them.

Shortfall (2021-2022)

Health workers at Sub Centres, PHCs, CHCs – 2288

Specialist – 2398

Radiographer – 680

Lab technician – 1564

Nursing Staff – 2134

A hospital sanitized for VIP visit

Post the stampede incident, the Deen Dayal Upadhyay Joint Hospital in Aligarh has become a hub for VIP visits and media interactions. The vicinity of this freshly painted building is clean and spacious.

The staff is ever smiling, never hesitating to speak to the media. “Covid had prepared us for such emergencies, ” they said.

“We received patients with fractures in their ribs,” said Rose Mary, head of the Nursing Staff. One attendant was extremely eager for us to film the emergency ward, where the six injured patients were kept. The now-empty beds have spotless, unwrinkled sheets. Most patients had been discharged within 24 hours of the event, with the last discharge occurring early on the morning of July 4. “The relatives wanted to take their patients home,” said Rose Mary.

The hospital staff is ever-ready to speak to the media, but friendly off the record conversations soon give way to murmurs of disgruntlement about staff shortage and the unfair system of contractual doctors.

On the hospital porch, Advocate AP Singh, representing Bhole Baba, faced a barrage of questions from the media. Singh deflected blame, asserting, “This isn’t Baba’s fault. Show me one video [of wrongdoing].” Singh offered limited appeasement, saying, “Baba will take care of his devotees” and promising financial aid to the affected. He also proposed a mourning event for the deceased followers. When asked why lakhs of followers were allowed to congregate without adequate precautions he said: “When Hindus are called “hinsak”, it is inevitable that the community will come out in support of Sanatan.” (Referring to Rahul Gandhi’s jibe at the BJP in Parliament) Interestingly, Singh concluded by thanking “Yogiji for the efficient handling of the situation.”

When our team brought to his attention reports of ambulance and oxygen shortages, and how families had to scramble to collect the bodies of their loved ones, he responded by saying, “It’s impossible to predict such emergencies and to be prepared for it.” However, it’s precisely during such emergencies that the deplorable state of healthcare in the state comes under scrutiny.

The lack of preparedness is not a new phenomenon in Uttar Pradesh. In 2017, the state-run BRD Medical College hospital in Gorakhpur witnessed a tragic incident where numerous child deaths occurred due to a shortage of oxygen supply. The incident drew national attention, with 63 children dying due to lack of oxygen.

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed the state’s healthcare inadequacies, with Uttar Pradesh struggling to cope with the surge in cases. And now, the recent tragedy in Hathras has once again highlighted the same. There were reports of difficulties in collecting and transporting the bodies of the stampede victims to their families. Some families reportedly had to wait for hours, even overnight, to receive the bodies of their loved ones. The situation was further complicated by the lack of proper identification and documentation of the bodies, adding to the distress and anguish of the families. Is it then any surprise that people in the state are drawn to the promise of magical cures offered by Godmen?

PS: What caused the deaths?

Autopsy reports from Agra and Etah government hospitals revealed that asphyxia due to chest compression was the primary cause of death in the Hathras stampede. The reports also showed that blood accumulation in the thoracic cavity, rib injuries, and chest injuries contributed to the high number of casualties. Most of the deceased were women between 40-50 years old. Seven were children. The district hospital in Etah performed an unprecedented number of autopsies, with 27 bodies brought to the mortuary, four times the usual number.